Echoes of Freedom: The Untold Stories of African Americans in Arlington's Section 27

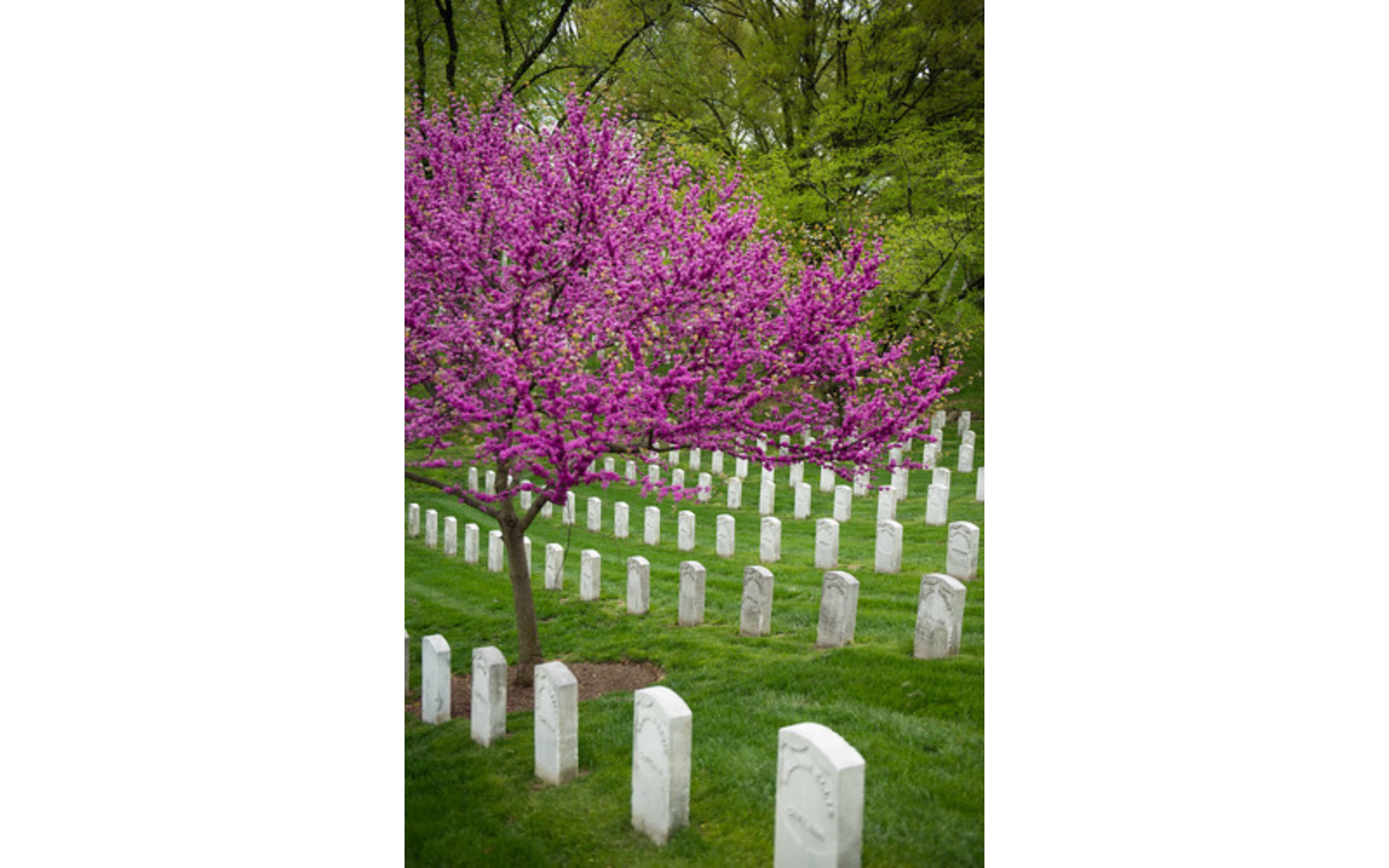

Arlington National Cemetery serves as the final resting place for more than 400,000 individuals. Most are veterans. But one of Arlington’s lesser-known stories is that of Section 27, the resting place documenting the nation’s complicated history of slavery, freedom and military service.

(Editor's Note: As the nation observes Veterans Day, Atlantic City Focus takes this time to celebrate the contributions of African American soldiers who have valiantly served in America's Armed Forces. Today, we tell the story of Section 27 in Arlington National Cemetery.)

ARLINGTON – Arlington National Cemetery is one of America’s most famous burial grounds. However, it's more than a resting place for military heroes. It's a microcosm of society filled with individual stories of resilience, independence, and sacrifice.

One of Arlington’s lesser-known stories is that of Section 27, the resting place which reveals the nation’s complicated history of slavery, freedom and military service.

Sign Up for Atlantic City Focus Weekend Guide

Your Key to Winning the Weekend in AC and Beyond!

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

A Section Rooted in Freedom

Tucked in the northeastern corner of the cemetery, Section 27, became a burial ground for African Americans during the Civil War and beyond.

Ric Murphy speaks on Arlington National Cemetery's Section 27

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when confederate troops fired on South Carolina’s Fort Sumter. Although President Abraham Lincoln didn’t personally agree with slavery, emancipation was not the paramount issue, according to a letter he wrote to Horace Greeley, where he emphasized that his primary goal in the Civil War was to preserve the Union.

"If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that," Lincoln wrote.

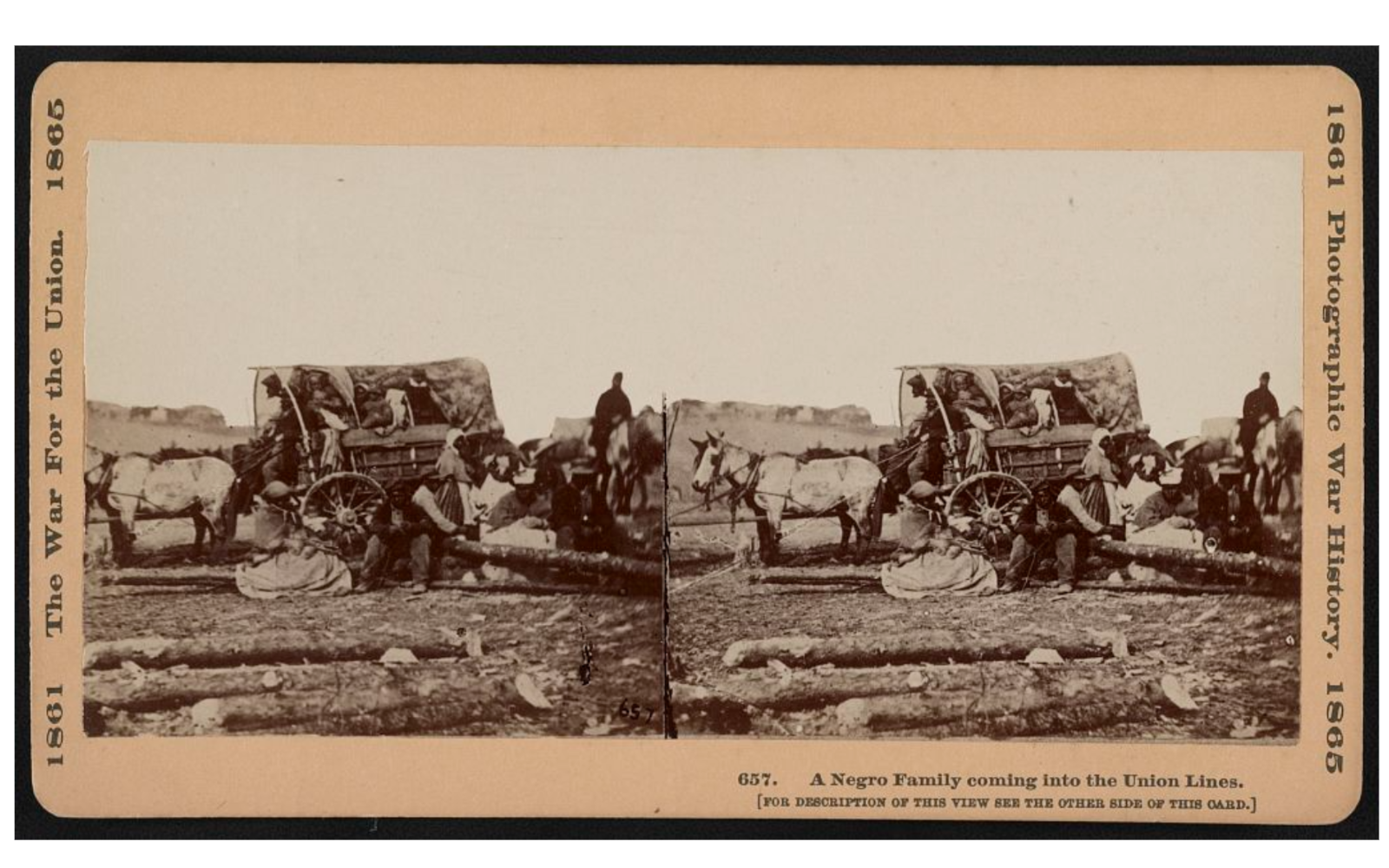

The President’s greater concern was collecting Federal Excise taxes, which the Confederacy defiantly refused to pay. Still, the Union government made provisions for freeing slaves under certain conditions. Under the Confiscation Act of 1862, slaves could be freed in three cases:

- Fugitive slaves who reached Union lines,

- Slaves captured from or deserted by their owners,

- Slaves living on Union-occupied territory that was previously Confederate-occupied territory.

This resulted in the human chattel being classified as “Contrabands of War.” As word reached Confederate-controlled areas, those who would rather be “contrabands” than slaves began escaping to Union strongholds in hopes of gaining their freedom, though many died en route, never experiencing the freedom for which they longed.

Between 1864 and 1867, more than 3,800 freed individuals found their final resting place there. Known then as “contrabands” — a term used expressly for formerly enslaved people who escaped to Union lines — these men, women, and children were marked with headstones simply inscribed with “citizen” or “civilian.” This symbolized their passage from enslavement to freedom.

As the war raged, wounded Union and Confederate troops, alike, were brought to hospitals near Washington D.C. However, so many soldiers died, that area cemeteries began reaching capacity, and by the third year of the war, 1864, Arlington National Cemetery had to be established. Arlington Plantation, the confiscated home of Union officer turned Confederate, General Robert E. Lee, was chosen as the new burial ground. Section 27 was established first.

Section 27 is also home to some 1,500 soldiers of the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.), who fought valiantly for the Union. These African American regiments, who faced the brutalities of war and systemic discrimination, made significant contributions to the Union’s success.

Their graves are distinguished by the Civil War shield and marked with “U.S.C.T.” to remind visitors of their bravery and dedication.

The Legacy of Freedman’s Village

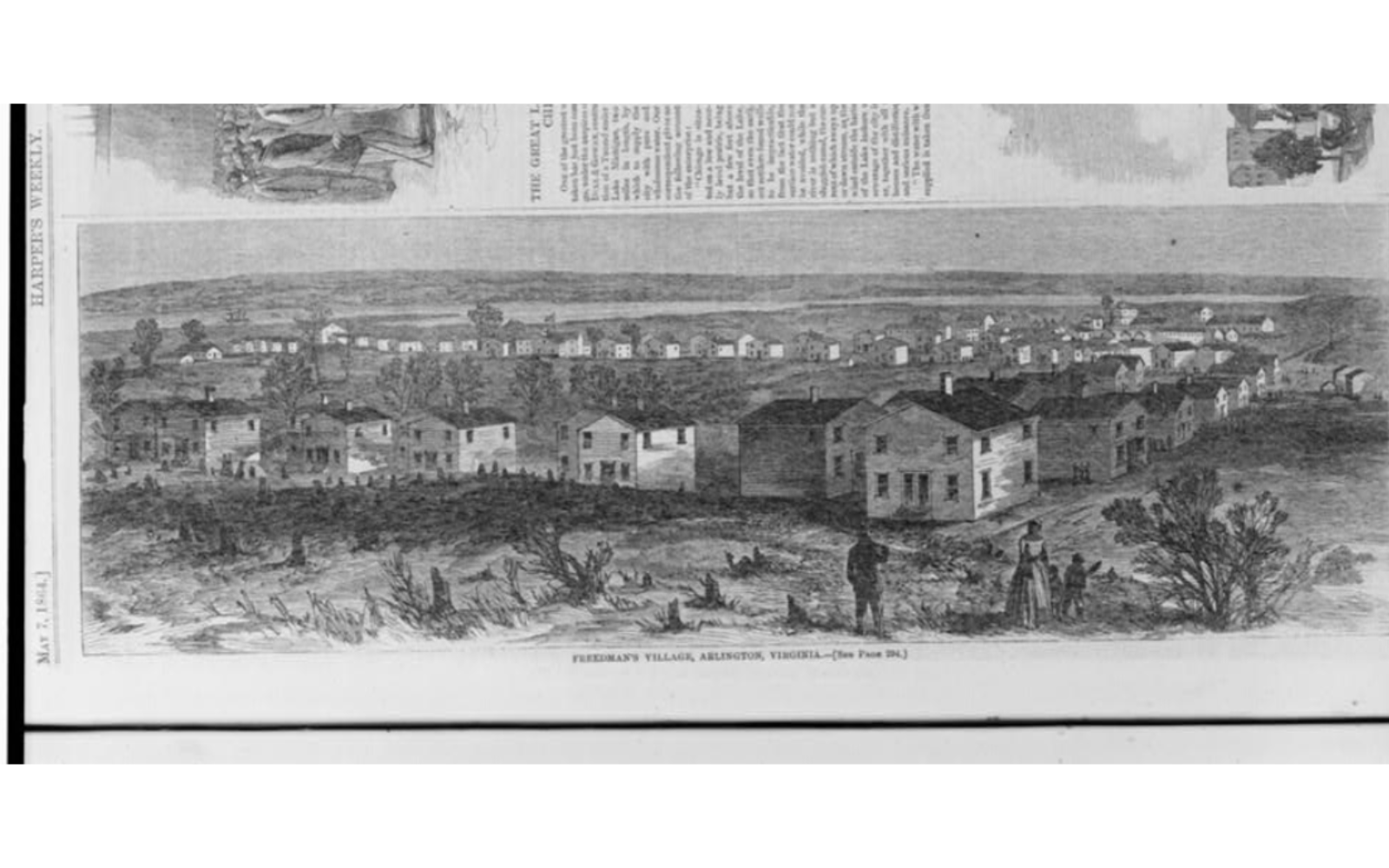

Just beyond the boundaries of Section 27 once stood Freedman’s Village, a government-established community that symbolized hope and new beginnings for freed African Americans. Created in 1863, the village offered housing, schooling, and training for employment, fostering a sense of stability amidst the uncertainty of Reconstruction. Though many of its residents contributed to building the nation, records suggest that none of them were buried in Section 27.

A Broader Recognition of Service

While Section 27 holds a special place in history, Arlington’s grounds tell a larger story of African American service. Scattered throughout the cemetery are graves of the legendary Buffalo Soldiers, all-Black regiments who served with distinction on the Western frontier following the Civil War. Their presence underscores the enduring legacy of Black soldiers who fought for a nation that far from embraced them.

Stories Carved in Stone

Arlington National Cemetery serves as the burial grounds for more than 400,000 individuals. Section 27 and the broader Arlington grounds are more than historical markers. They are monuments to resilience, independence, and sacrifice. The African Americans laid to rest there remind us that the path to freedom is paved with immense struggle and profound dedication.

In visiting Arlington National Cemetery, one steps into a living chronicle of the fight for liberty and justice, a journey that still echoes in the stories of those who rest beneath its hallowed ground.

Thanks for reading the whole story!

At Atlantic City Focus, we're committed to providing a platform where the diverse voices of our community can be heard, respected, and celebrated. As an independent online news platform, we rely on a unique mix of affordable advertising and the support of readers like you to continue delivering quality, community journalism that matters. Please support the businesses and organizations that support us by clicking on their ads. And by making a tax deductible donation today, you become a catalyst for change helping to amplify the authentic voices that might otherwise go unheard. And every contribution is greatly appreciated. Join us in making a difference—one uplifting story at a time!